I’ve been delivering a talk with the same title as this blog post for a few years now. It’s a popular talk, and a topic that’s close to my heart.

Here’s a video of the talk from DevBreak 2021, and the following blog post was originally written for Agile Meets Architecture, Berlin 2023.

Note: At the end of this post I present the “Stupidity Manifesto”, which you can sign here.

Once upon a time, there was a female software engineer. When she studied mathematics at university, she was one of a tiny minority of female students. That was the first time she internalised the idea that women can’t do the same things that men can do. The evidence was in front of her eyes. And it was there again when she switched to software engineering. In her first job, she was the only female developer. And compared to her colleagues, she was a late developer. It seemed they had all taught themselves to code as children and teenagers. But this was the mid 90s. She attended university in the early 90s, where she never owned a computer and barely used one until after she graduated.

A few years later, in her second software job, she kept asking to work on the more difficult, more interesting, code bases… but she was always denied. When she interviewed for a more senior position elsewhere, she was told she didn’t know enough. She wasn’t surprised. It confirmed all her worst suspicions about herself.

Twelve years into her career, she was laid off and it was a relief. She had never felt like she belonged. She didn’t want to work in IT any more.

Here’s a question for you: Do you ever have to Google anything related to your sphere of expertise? When you do, do you shame yourself for it? Do you feel as though you’re supposed to know everything, and there’s something wrong with you if you don’t?

If you feel this way, you’re not alone. The woman described above is me. But now I’ve been doing this for over 23 years, and I make a living out of teaching software engineering skills. Does this mean I’ve finally reached the “comfortably confident that I know all the things” stage of my career? Nope. Quite the opposite.

The more I learn, the better I understand how little I know.

These days, when I find myself beating myself up for my ignorance (and I’m sorry to tell you that I do still beat myself up), I remind myself that learning is a fundamental part of this profession. Rather than worrying because you still have stuff to learn, you should instead be concerned if you don’t.

But even when we know on some level that this is true, it’s not always what we tell each other. And as a result, we do untold damage by making each other feel stupid.

What if we didn’t do this? Imagine a world where you arrive at your desk each day excited about learning new things. Where you never worry that you don’t know enough. Where there is no such thing as imposter syndrome. Because it turns out that being an effective IT professional is not about what you know. But we think it is — and that causes problems.

Problematic behaviours

I left the industry because I felt inadequate and stupid. It seemed that everyone else knew more than me. But I do a lot of teaching these days, which means I’m now very aware of how common this feeling is, and I’ve noticed some behaviours that I believe make it worse for all of us. I run through all of them in my talk, and I’ll present the following key ones in this article:

- Laughing at others for gaps in their knowledge

- Talking in jargon

- Hiding a lack of knowledge

- Gatekeeping

Laughing at others for gaps in their knowledge

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve witnessed colleagues emerge from interviewing a prospective employee and saying things like “Can you believe, I just interviewed someone who didn’t even know what a Z was?” followed by incredulous laughter. Haha, what a doofus, fancy thinking they could get a job here if they don’t even know that.

For Z, you can substitute your favourite surely everyone knows about this item, and I guarantee I can find you somebody amazing, experienced and successful who knows nothing about it.

But it helps us bond with each other, right? If we can have a bit of a laugh about how stupid those other people are? And it doesn’t do any harm, because they’re not in the room. They don’t know we’re laughing at them. No, they don’t. But you do. I do. Everyone else in the room does. I’m certainly not the only person thinking, I must make sure I don’t become the next butt of the jokes. Instantly feeling stupid, as I consider all the things I don’t know enough about.

The worst thing about this is, I’m likely to handle this problem by taking steps to hide my ignorance. I’ll join in the next round of laughter extra loud, to prove I’m one of you clever people and not one of those stupid ones. I won’t ask questions to clarify crucial details. And I will find myself increasingly…

Talking in jargon

This is another one that can help us to bond with each other and feel clever, but it comes at the cost of making others feel stupid. Every time you make assumptions about what jargon others will understand, or even worse, judge them for not knowing the same jargon as you, you make it less likely they’ll ask for clarification. It becomes more likely that gaps in communication will widen, and your product will not behave the way people expect or need it to behave.

And of course, not only do people avoid asking for clarification, they take active steps towards…

Hiding a lack of knowledge

Of course we all do this. We avoid “asking stupid questions.” We exaggerate what we know in job interviews and on CVs. We don’t admit it when we find ourselves in meetings where we have little or no idea what anyone is talking about. It’s just self preservation, right?

The more we work in environments where knowledge is considered to be a good indicator of our colleagues’ proficiency, the more likely we’re not being honest with each other about what we know. The last time I was in the market for a new job, I reached a point where if I saw companies imply that they possessed advanced techniques for filtering out only the very best and rejecting the rest, I automatically rejected them. Because in those kinds of environments, people will go to advanced lengths to prove they are indeed the best… which means never admitting any weakness and therefore covering up the unavoidable fact that they don’t know everything.

Are these people happy and confident? No. They are likely peddling furiously underwater and permanently paranoid that someone will find them out… for what? For being stupid? Well yes, that’s what it feels like. But what they’re really in danger of revealing is their own basic humanity.

And of course, the kind of culture I’ve described above, the kind I came to deliberately avoid when looking for good companies to work for, is that of…

Gatekeeping

This is where we decide that we are special, and large swathes of the rest of the profession are not, and all we need is to perfect our formulas for identifying the pearls and rejecting the swine. And what does it do? Yep. It makes us all feel stupid, terrified as we are that we will come up against these standards and fall short.

Solutions

So, what can we do to address these problematic behaviours?

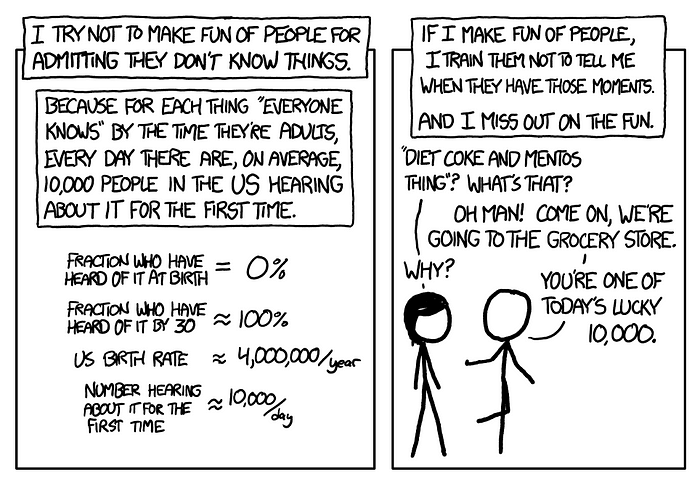

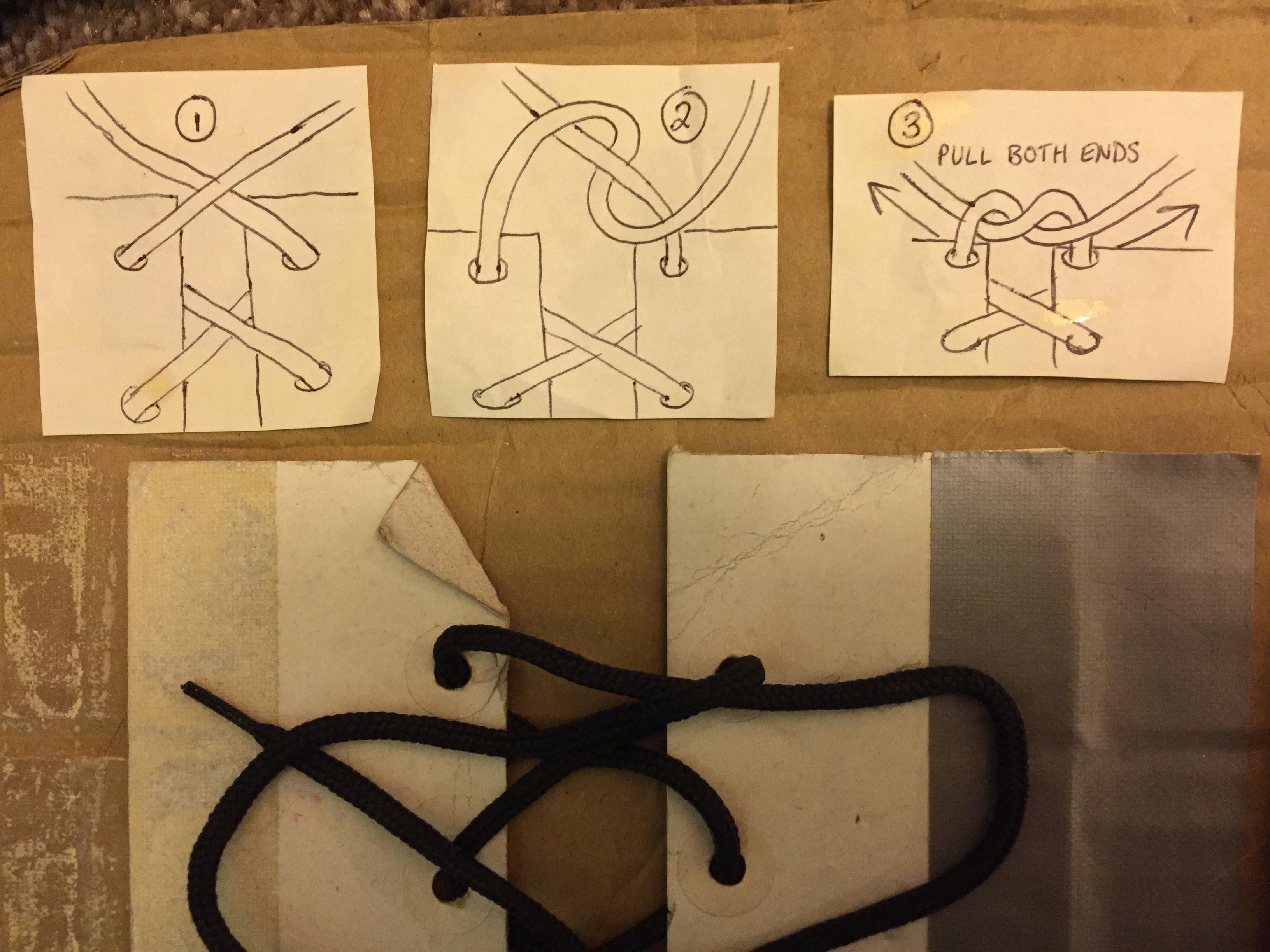

The Lucky 10,000

As described in xkcd’s excellent cartoon above, today’s lucky 10,000 will learn something exciting and new. And the rest of us have a choice: Embrace that journey and travel with them, or stand on the sidelines laughing at them for not having learnt it yet.

Making that decision to get excited about the learning our colleagues have yet to do, is about a lot more than individual choices in single moments. It’s about recognising that the range of knowledge in our industry is very wide. It’s wide, and it’s widening exponentially all the time. You could take two respected professionals with long successful careers, and find no overlap in their knowledge. Hell, you could find a busload of them with no overlap. It’s pointless to wring our hands over what people don’t know, and much more enlightening to embrace the learning of our colleagues and ourselves.

They don’t know as much as you think they do

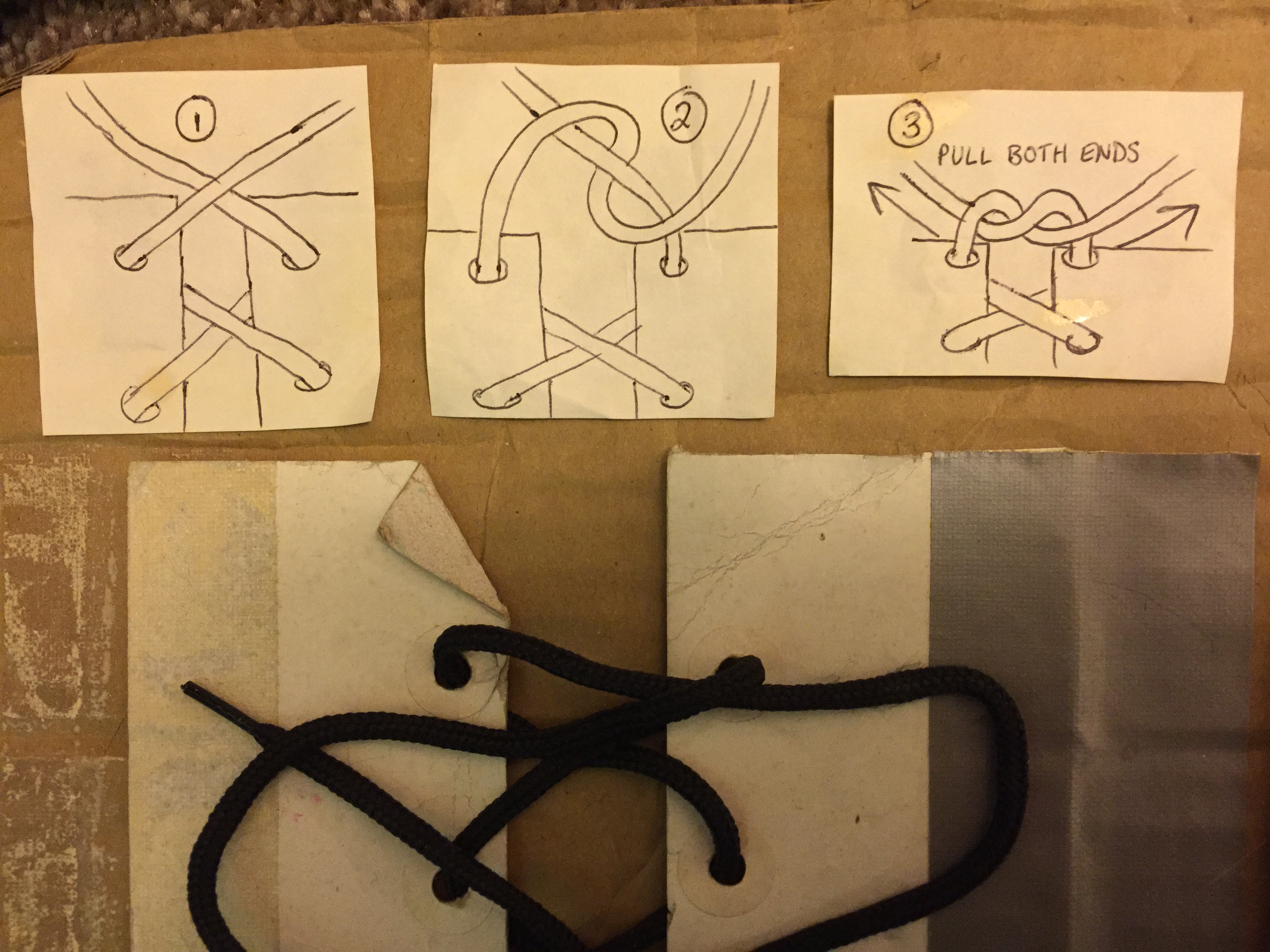

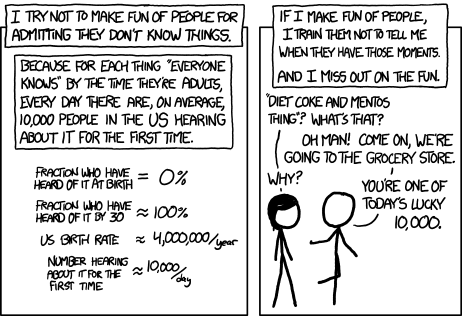

I use this series of graphics a lot in my talks. Here I show only four of the images, but it’s enough to illustrate the point: When you look at an internal message board where your colleagues are discussing a range of subjects, it’s tempting to think to yourself, “Oh my, all these people are so knowledgeable and confident on all of these subjects, and I don’t know about any of them.”

But of course each one of those people is only posting confidently about some of those topics, maybe only one each, and chances are you have posted knowledgeably yourself on at least one of them. And they are likely suffering the same worries and insecurities as you are, looking at each other — and you — and thinking how much less knowledgeable they are than everyone else.

You’re not doing anyone any favours — least of all yourself — when you assume people know more than they do. We can all benefit from being realistic about each other’s capabilities.

Be confident in your own ignorance

At the start of this piece, I talked about how I ran away from this industry in relief, glad to be laid off and determined never to return. But a few years later I found myself in need of a new job, and recognising that despite having not previously valued them, those twelve years of engineering experience were worth something to me.

I returned to this industry, but this time with a different approach. In the intervening years I’d been working for a lower salary as a high school maths teacher, so it wasn’t hard to return to technology at entry level, joining all the new computer science graduates and behaving as though as I was brand new. This gave me a new lease of life. I wasn’t pretending to know anything I didn’t, but I was excited and eager to learn. I let go of any shame and made a point of asking simple questions.

Of course those previous twelve years did count for something, and it wasn’t long before I found myself in senior leadership positions. And it was something of a revelation to me that the more open and confident I was about what I didn’t know, the more people respected me.

Not only did it help me to progress and learn quickly, it also helped those around me to do the same. When senior figures ask simple questions and show no shame about what they don’t know, everyone around them is empowered to do the same. Everyone feels less stupid, and their knowledge and competence increase more quickly as a result.

I’ll leave you with what I call…

The Stupidity Manifesto

[If you’d like to sign the manifesto, you can do that here.]

LET’S STOP MAKING EACH OTHER FEEL STUPID. Instead, let’s…

- ENCOURAGE EVERYONE TO ASK QUESTIONS

- Lead by example: Be honest when we’re confused

- Value curiosity over knowledge

- Prioritise clarity over jargon

- Remember we all forget stuff

- Get excited about teaching and learning

- Acknowledge the broad range of knowledge in our industry, and avoid judging someone if their knowledge doesn’t match ours

- LET’S STOP MAKING EACH OTHER FEEL STUPID.

If you’d like to sign the manifesto, you can do that here.